Our Company

Locations

Contact Us

Newsletter

Sign up to receive email updates on the latest products, collections and campaigns.

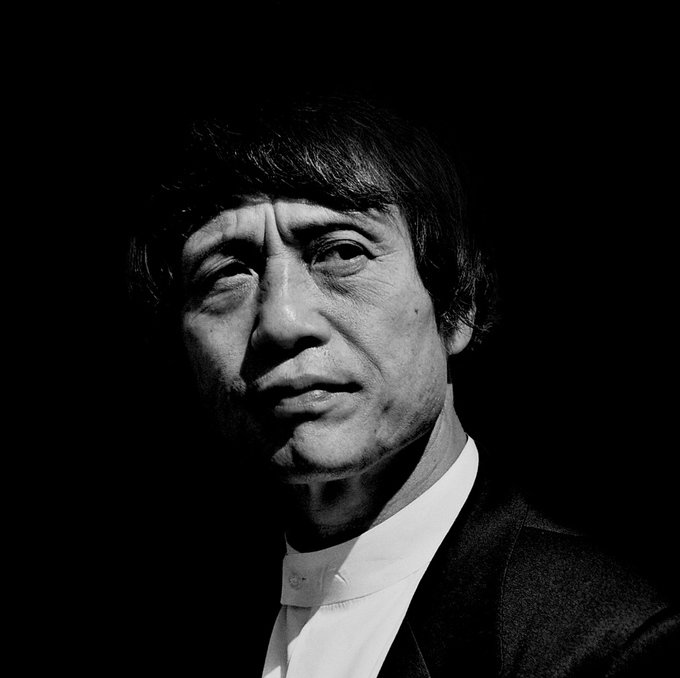

Tadao Ando is one of the most relevant names in contemporary Japanese architecture. He was born in Osaka in the middle of World War II (1941). Self-taught and an enthusiast of the Le Courbusier style, his postmodern mood, sober and clean, is undoubtedly attached to the ancestral traditions of Japan. The interaction of the natural elements with the materials is another characteristic that has more presence in his constructions.

Tadao Ando is one of the most relevant names in contemporary Japanese architecture. He was born in Osaka in the middle of World War II (1941). Self-taught and an enthusiast of the Le Courbusier style, his postmodern mood, sober and clean, is undoubtedly attached to the ancestral traditions of Japan. The interaction of the natural elements with the materials is another characteristic that has more presence in his constructions.

Curious and keen-sighted he was formed mainly during his trips to the United States, Europe, and Africa between 1962 and 1969. In them he immersed himself in the information coming from the buildings of Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Louis Kahn. These influences would encourage him – upon his return to Japan (1968) – to open his firm Osaka Tadao Ando Architects & Associates.

Fame and recognition would come after 20 years of hard work and perfecting his own style. In his first work, the Azuma House, Tadao Ando takes the early steps of his interesting relationship with the elements, creating a patio designed for the “game of wind and light.” With this he dared to challenge the principle of “ease and comfort” present in the Japanese urban architecture of that time and used this courtyard to communicate three spaces, making light and air flow.

Fame and recognition would come after 20 years of hard work and perfecting his own style. In his first work, the Azuma House, Tadao Ando takes the early steps of his interesting relationship with the elements, creating a patio designed for the “game of wind and light.” With this he dared to challenge the principle of “ease and comfort” present in the Japanese urban architecture of that time and used this courtyard to communicate three spaces, making light and air flow.

His internationalization came in the 1980s. Established as the supreme exponent of the new Japanese architecture, soon works such as the Rokko housing complex (1983-1993) and the Chapel on Mount Rokko (1986) began to attract attention. But it is the individualized play of light and the constant, almost obsessive, use of concrete -which is palpable in the Church of Light (1989) – is what makes his works the object of study in universities and schools of design.

The 90s brought the possibility of the ephemeral to Ando’s portfolio. Thus, his nation put in his hands the creation of the pavilion that would represent them in the Seville Expo ‘92.

The work that was at that time the largest wooden building in the world, was also cataloged as the best of the Expo. And so the Kinari achieved its mission in Seville: to take the visitor through the flow of Japanese culture and catapulting its creator.

Another memorable work of that decade is the Forest of Tombs Museum, in which, according to its maker, he sought to create an environmental museum that incorporated not only the tombs scattered at the place, but also the natural environment of funeral mounds. The work located in the archaeological park of Fusoki-no-Oka, in Chikatsu-Asuka, south of the Osaka prefecture, pays homage to Prince Shotoku (574-622), who established the principles of civilian government in Japan. So again, the austerity of the concrete took a leading role in the middle of a fertile flatland surrounded by cherry and plum trees.

Another memorable work of that decade is the Forest of Tombs Museum, in which, according to its maker, he sought to create an environmental museum that incorporated not only the tombs scattered at the place, but also the natural environment of funeral mounds. The work located in the archaeological park of Fusoki-no-Oka, in Chikatsu-Asuka, south of the Osaka prefecture, pays homage to Prince Shotoku (574-622), who established the principles of civilian government in Japan. So again, the austerity of the concrete took a leading role in the middle of a fertile flatland surrounded by cherry and plum trees.

This same decade saw him awarded with the Pritzker (1995) for his design of the Nagaragawa Convention Center, an award that was added to the Prize of the Architectural Institute of Japan (1979), the Cultural Design of Japan Prize (1983), the Prize of the Finnish Association of Architecture (1985), and to the one granted by the French Academy of Architecture (1989)

He has also received other awards during his meteoric career, including Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters (French Republic, 1995), Official of the Order of Arts and Letters (French Republic, 1997), Knight of the Order of Culture (Empire of Japan, 2010), and Grand Officer of the Order of the Star of Italy (Italian Republic, 2013).

Concerned about his legacy, in a recent interview he said that his focus is on conceiving a universe where the old and the new coexist, and thus contribute “even a little, in this wonderful process of transmission.” Perhaps that is why, with more than 75 years in tow, the former boxer who hanged his gloves to embrace concrete and architectural lines is currently working on the rehabilitation and transformation of the Punta della Dogana Museum in Venice and the recovery of the Bourse de Commerçe in Paris, both projects to be inaugurated in 2018. Apparently his motto is to build until the concrete holds up.

Sign up to receive email updates on the latest products, collections and campaigns.

Carrera 9 Nº80-45

Bogotá D.C., Colombia

Monday to Friday: 11:00 a.m. - 07:00 p.m.

Saturday: 11:00 a.m. - 06:00 p.m.

(+571) 432.7408/7493

Calle 77 #72-37

Barranquilla, Colombia

Monday to Friday: 08:00 a.m. - 06:00 p.m.

Saturday: 09:00 a.m. - 01:00 p.m.

(+57) 605 352 0851

Edificio La Cuisine

Costado Suroeste, C.C. La Paco

Escazú, Costa Rica

Monday to Friday: 09:00 a.m. - 05:00 p.m.

Saturday: 10:00 a.m. - 04:00 p.m.

(+506) 4000.3555

Galerías de Puntacana No. 51

Punta Cana, La Altagracia, R.D.

Monday to Friday: 09:00 a.m. - 06:00 p.m.

Saturday: 10:00 a.m. - 01:00 p.m.

(809) 378.9999

C/Rafael Augusto Sánchez No.22,

Piantini, Santo Domingo, R.D.

Monday to Friday: 09:00 a.m. - 06:00 p.m.

Saturday: 09:00 a.m. - 01:00 p.m.

(809) 378.9999

18187 Biscayne Bvld., Aventura

FL 33160

Monday to Friday: 10:00 a.m. - 06:00 p.m.

Saturdays by appointment.

(786) 322 5432

www.lacuisineappliances.com

sales@lacuisineappliances.com

3232 Coral Way,

Miami FL 33145

Monday to Friday: 10:00 a.m. - 06:00 p.m.

Saturday: 10:00 a.m. - 03:00 p.m

(305) 442-9006

www.lacuisineappliances.com

2005 NW 115th Avenue

Miami, FL 33172

Monday to Friday: 09:00 a.m. - 05:30 p.m.

Saturday: Closed

(+1) 305 418.0010

info@lacuisineinternational.com

Obarrio. Av. Samuel Lewis,

Addison House Plaza,

Local No.11, Panamá

Monday to Friday: 09:00 a.m. - 06:00 p.m.

Saturday: 10:00 a.m. - 04:00 p.m.

(+507) 265.2546/2547

Av. Caminos del Inca 1603,

Santiago de Surco, Perú

Monday to Friday: 10:00 a.m. – 07:00 p.m.

Saturday: 10:00 a.m. – 01:00 p.m.

(+511) 637.7087

Centro Comercial San Ignacio, Nivel C, local No.5

Caracas, Venezuela

Monday to Saturday: 10:00 a.m. – 07:00 p.m.

(+58) 212 264.5252

(+58) 414 018.5352 (Wholesale)

ventas@lacuisineappliances.com

Complejo Pradera Ofibodegas No.13,

20 calle final Z. 10 Km. 6.8 Carretera a Muxbal,

Santa Catarina Pínula, Guatemala

Monday to Friday: 08:00 a.m. - 05:30 p.m.

Saturday: 09:00 a.m. - 12:30 p.m.

(+502) 6671-3400